For a full-time nerd like me, reading is a professional hazard. Maybe you know what I mean.

But to be honest, I love it. Every morning, I get to start my day reading a couple of books from my ever-growing “to-read” pile. Then, throughout the course of the day, I peruse and dive deep into articles and essays relevant to whatever it is I am researching or writing at the moment. Then, as I settle onto the corduroy couch in our living room for the evening, maybe with a cup of tea or a tumbler of whiskey at hand, I read something “for fun” — whether that be a Krimi or international literature or a non-fiction book that has nothing to do with what I’m working on.

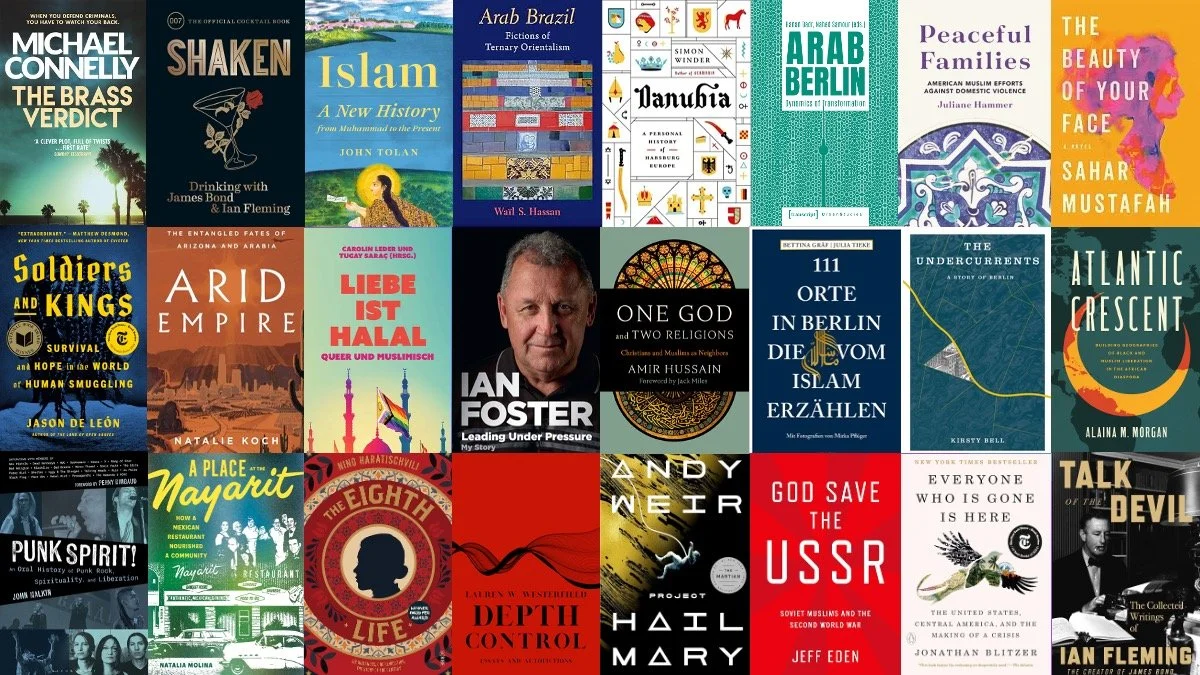

This year, that meant I read over 23,000 pages and 75 different books. And, as is my custom at the end of each year, I highlighted 25 books that stood out for me in 2025.

These books were not all published in 2025, but I read them this year and list them in the order I finished them. Some of them, actually, have yet to be released. They cover the usual themes that draw me in: storytelling, religion, Berlin, James Bond, rugby, Los Angeles, and living in an age of discord, diversity and difference.

Perhaps you will find your next read below. Or, maybe you enjoyed the same book as me in 2025. Either way, take a look at the list and let me know if you have any recommendations for 2026.

📖 The Brass Verdict — Michael Connelly

A sharp legal thriller rooted in Los Angeles. I love Connelly’s morally-complex storytelling, procedural rhythm, and attention to justice under pressure—revealing a narrative craft that respects both character and consequence.

📖 Shaken: 007 Cocktails

A playful, stylish dive into James Bond culture through mixology. It blends pop history, design, and espionage flair—perfect for my affection for Bond’s global imagination, time-capsule like nature and escapism.

📖 Islam: A New History — John Tolan

A lucid, global history of Islam. I value its narrative breadth, attentiveness to diversity, and ability to situate religion within lived historical complexity. As I wrote for Publisher’s Weekly: “Tolan’s impressive geographic scope and fine-grained historical detail combine for a masterful portrait of Islam as a religion and culture. The result is [a] definitive history.”

📖 Arab Brazil — Waïl Hassan

An illuminating portrait of Arab diasporic life in Brazil, Hassan’s work provides a careful interrogation of popular fiction and mass media melodramas to undergird his insightful theorization of what “ternary Orientalism” is and how it functions.

📖 Danubia — Simon Winder

A witty, learned journey through Central Europe’s tangled history. I’m drawn to its playful storytelling, attention to place, and ability to make borders, empires, and cultures feel alive. I’m a sucker for anything Simon Winder writes and this one was no exception.

📖 Arab Berlin — Hanan Badr and Nahed Samour

A compelling account of Arab life in Berlin. It combines urban history, religion, media, commerce and migration—key themes for understanding contemporary Europe and the city I continually return to intellectually.

📖 Peaceful Families: American Muslim Efforts Against Domestic Violence — Julianne Hammer

A thoughtful exploration of how Muslim American organizations address domestic violence within their communities, family life, and according to principles and practices of faith. I appreciate its grounded approach to religion, ethics, and everyday practice in the context of U.S. identity politics.

📖 The Beauty of Your Face — Sahar Mustafah

A powerful novel of Muslim American life, trauma, and grace. Its emotional depth and narrative courage exemplify storytelling that confronts the realities of life while affirming dignity and faith.

📖 Soldiers and Kings — Jason De León

A haunting account of those who traffic in migrants, shaped by the ever-present specter of survival in American political orders of exception and excess. I value its riveting storytelling and character development, anthropological rigor, and refusal to let readers look away from the human cost of U.S. immigration politics.

📖 Arid Empire: The Entangled Fates of Arizona and Arabia — Natalie Koch

A sharp analysis of power, climate, and geopolitics in the deserts of Arizona and the Gulf. It blends geography, politics, and narrative insight—essential for understanding modern empire and environmental futures.

📖 Liebe ist Halal — Carolin Leder und Tugay Saraç

A culturally rich exploration of love, law, the weight of history, and navigating Muslim life in contemporary Germany. I admire its engagement with Berlin, belonging, and the everyday negotiations of faith, being, and belonging.

📖 Leading Under Pressure: My Story — Ian Foster

A rugby coach’s memoir about leadership and resilience. As a rugby fan, I appreciate its reflections on teamwork, humility, and performing faithfully under immense expectation.

📖 One God, Two Religions — Amir Hussain

Amir Hussain was key to my development as a scholar (and a human being). This is a generous, accessible guide to Christian-Muslim theological kinship that continues to shape me. I value its bridge-building spirit, clarity, and commitment to interreligious understanding grounded in lived faith.

📖 111 Orte in Berlin, die vom Islam erzählen — Bettina Gräf und Julia Tieke

A fascinating guide to Islamic narratives embedded in Berlin. It combines place-based storytelling, urban memory, and religious diversity—precisely the Berlin I want others to see.

📖 The Undercurrents — Kirsty Bell

Another Berlin book, this is an essayistic meditation on Europe’s layered histories through the story of a woman in transition. I’m drawn to its reflective style, attention to place, and ability to uncover submerged cultural narratives.

📖 Atlantic Crescent — Alaina Morgan

How do you imagine different worlds? According to historian Alaina Morgan, for African descended – or Black – people in the twentieth-century Atlantic sphere, it meant drawing on anti-colonial and anti-imperial discourses from within and beyond the worlds of Islam to “unify oppressed populations, remedy social ills, and achieve racial and political freedom.”

📖 Punk Spirit! — John Malkin

Punk rock played an outsized role in my political and spiritual awakening. So, I jumped at the opportunity to be part of Malkin’s new book. Here’s my blurb on his forthcoming book, which is fantastic: A skilled interviewer, John Malkin is one of a handful of punk mavens willing to explore its deep, spiritual intimations. This is a monumental collection of conversations, offering anyone with a reasonable curiosity about punk rock and spirituality the opportunity to understand their amorphous, vibrant, and sometimes revolutionary entanglements. If God is dead, punk is not dead, and the anti-establishment postures and rebellious spirit captured in Malkin's book lives on!

📖 A Place at the Nayarit — Natalia Molina

An intimate history of a Mexican restaurant as a social world. It exemplifies microhistory at its best—exploring migration, race, place-making, and belonging through the story of a single restaurant in downtown Los Angeles.

📖 The Eighth Life — Nino Haratischwili

An epic family saga spanning generations and empires. I admire its ambitious storytelling, moral seriousness, and ability to render history personal and unforgettable. Was unputdownable as I traveled in Georgia earlier this year.

📖 Depth Control — Lauren Westerfield

An immersive collection of writing and essays that blends emotional depth with searing, almost uncomfortable, honesty. Westerfield’s prose is confident and atmospheric, punchy and wryly humorous, drawing readers into a highly personal narrative of life as it is, leaving you with feelings that linger well after the final page.

📖 Project Hail Mary — Andy Weir

A hard-science fiction story of friendship and survival. I enjoy its humor, optimism, narrative ingenuity, and belief that curiosity and cooperation can save worlds.

📖 God Save the USSR — Jeff Eden

A fascinating and meticulously researched exploration of religious life and policy in the Soviet Union during and after World War II. Eden deftly shows how Islamic practice persisted and adapted within an officially atheist state, offering fresh insight into the complex relationship between religion and power.

📖 Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here — Jonathan Blitzer

A deeply humane account of migration in the broader landscapes of the U.S. borderlands. I value its narrative approach to journalism, moral clarity, and insistence on seeing migrants, and those who craft policy or enforce laws around them, as fully human beings.

📖 Talk of the Devil: The Collected Writings of Ian Fleming — Ian Fleming

A treasure trove for Bond enthusiasts. Beyond espionage, it reveals Fleming as stylist, traveler, friend, and observer of life—deepening my appreciation for the cultural world behind 007.

📖 Getting Through What You’re Through — Tanner Olson

Technically not out yet, this book of poetry and essays reminds us that while life is hard, promise might just be around the corner. With disarming empathy and lucent humor, Tanner gives us words of resilient hope — reminding us to notice the grace of small moments and the goodness tomorrow may yet bring.