Humans have long been drawn to space as part of our search for meaning, significance and security. But what if space could be the source of our salvation?

It is this question that led Brandon Reece Taylorian, widely known by his mononym Cometan, to start a new religion: Astronism.

From astrology to astrotheology, from questions of how to practice religions ensconced in Earth’s realities and rhythms to the context of outer space or life on other planets to the creation of new religious movements, spirituality and space exploration have long been intertwined.

It is Astronism, perhaps, that has taken the relationship between outer space and religion to its logical limit. At the age of 15, Cometan began to craft an astronomical religion that “teaches that outer space should become the central element of our practical, spiritual, and contemplative lives.”

“From my perspective, how religion and outer space intersect is crucial to understanding the future of religion,” Cometan, who is also a Research Associate at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, told me. “Outer space is the next great frontier that will reshape the human condition, including our religions.”

To that end, Cometan has contemplated how space exploration might produce new forms of insight, revelation and spiritual experience.

“The further we dare to venture beyond Earth, the more our beliefs about God and the universe will transform. I think that we need new and bold religious systems that will inspire our species to confront and overcome the challenges of the next frontier,” he said.

“As an Astronist, I define outer space as the supreme medium through which the traditional questions of religion will be answered.”

In this edition of “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I feature a Q&A with Cometan about Astronism and what we might have to learn about religion – and how we define and study it – through his experience founding a new tradition drawn from the stars.

Is The Christian Right Coming For Europe?

If you’re anything like me, you pay attention when an e-mail is marked “URGENT!!”

The particular e-mail I have in mind carried a subject line that was direct and equally attention-grabbing: “Christian nationalism is coming for Europe.”

The content was a single link, to an article written by United States journalist Katherine Stewart for The New Republic on the rise of the Christian Right in the United Kingdom. In it, Stewart tells of how she believes a form of hyper-patriarchal, homophobic and nationalistic Christianity often associated with evangelicals in the US is gaining a beachhead in the UK. The developments there, she writes, “are like a window on the American past.

“This is how things must have looked before the antidemocratic reaction really took hold,” she wrote.

As a correspondent covering European Christians and as a scholar teaching religion in Germany, I’ve tracked some of the developments, institutions and movements Stewart cites. While rumors of the Christian right’s rise in Europe need to be taken seriously, it is also vitally important that the careful observer of religion take note of some of the complexities that have shaped the Christian right’s contours in ways distinct from, if related to, the forms we see taking hold in the U.S.

Can AI Understand Religion? Students Put It To The Test

Ask E.B. Tylor what religion is and he would say it is, “belief in Spiritual Beings.”

Ask William James and he will tell you it is the “feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude.”

Ask Catherine L. Albanese, and she would say it is “a system of symbols (creed, code, cultus) by means of which people (a community) orient themselves in the world with reference to both ordinary and extraordinary powers, meanings, and values.”

Ask Émile Durkheim, Clifford Geertz or others, and you’d get a different answer from the perspectives of sociology, anthropology, theology, philosophy and more.

But what if you ask ChatGPT?

Well, you get a mix of the above, it turns out.

When I asked my friendly, neighborhood artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, it defined religion as, “a system of beliefs, practices, symbols, and moral codes that connects individuals or communities to the sacred, the divine, or some ultimate reality or truth.”

In the wake of ChatGPT’s viral launch in 2021, the question of how to integrate AI into the classroom — and the religious studies classroom at that — has been at the forefront of educators’ minds. With the global expansion of machine learning, big data, and large language models (LLMs), AI has the potential to radically impact teaching and learning, revolutionizing the way students interact with knowledge and how educators engage course participants.

There are, however, significant concerns about its ethical use, technology infrastructures, and fair access.

In this post, I share how I recently used AI as part of my pedagogy to help prompt deeper understanding of religion in the United States – and what we might have to learn from chatbots about how we define and discuss religion.

The AI Unessay

AI is a technology that enables machines and computers to emulate human intelligence and mimic its problem-solving powers.

The umbrella term “AI” encompasses various forms of machine-based systems that produce predictions, recommendations or content based on direct or indirect human-defined objectives. Based on

LLMs, AI generators like ChatGPT, Jasper or Google Gemini are tools that have been trained on vast amounts of data and text to provide predictive responses to requests, questions and prompts inputted by users like you, me or our students.

As with other advances in technology — from mobile phones and social media to enhanced graphics calculators and Wikipedia — educators have responded to AI in various ways. Some have moved quickly to ban its use and bemoan the submission of essays and other coursework clearly created with the help of AI.

Others have moved to integrate AI into their religious studies pedagogy, inviting students to create videos or infographics with the assist of AI to explain the elements, and role, of rituals to stimulate class discussion or to treat “AI as a tool for lessons that go beyond academics and also focus on the whole person.”

When I recently taught a course on American religion, I decided to assign what I called an “AI Unessay.”

The usual unessay invites students of varying learning modalities and expressions to create final projects that demonstrate their grasp of course material and discussions beyond the traditional essay. These can be hands-on demonstrations, mini-documentaries, artistic visualizations, performative projects or social media campaigns.

The AI Unessay invited course participants to design a set of prompts for an AI generator (e.g., ChatGPT) to write a 2,000-word essay on a topic in American religion, broadly defined. Then, participants were asked to write their own critical response to this AI essay, analyzing its strengths, weaknesses, sources and the process itself.

AI’s Religious Illiteracy

Students chose a variety of topics to cover, from religious themes in metal music and superhero comics to the “trad wife” trend among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and digital seances.

Throughout the semester, I worked with participants to refine their topic selections, come up with AI prompts and conduct secondary-source research and firsthand “digital fieldwork.”

Meanwhile, course lectures and readings were provided to supply helpful context on how each of these themes might be better placed within the wider currents of American religion and its

In a recent classroom experiment, students found, like many others, that AI responses were often biased, inaccurate, or even harmfully ignorant. | Image created in Meta AI for Patheos.

intersections with U.S. politics, economics and society.

Not all course participants opted for the AI Unessay. Others wrote traditional papers or put together a different kind of creative final project. But the majority of students opted for the AI-based project, saying they not only wanted to learn more about how to productively, and critically, work with AI, but wondered whether the technology was up for the challenge of understanding, parsing out and pontificating on America’s religious diversity.

Though participants did learn some new information from the AI essays and discovered some data they hitherto were unaware of, they were — on the whole — disappointed with the results. They found, like many others, that AI responses were often biased, inaccurate or even harmfully ignorant.

They also found that citations and sources were a decidedly mixed bag, with the chatbots often manufacturing fake data and made-up books or articles.

And finally, numerous students reflected that it was a challenge to get the AI chatbot to write at the appropriate length (2,000 words). The technology was often too efficient, churning out well-structured, but far too brief, answers to questions about metal music’s spiritual intimations or the nuances of the “trad wife” trend on TikTok. When asked to elaborate, participants found AI was overly repetitive or even fabricated false information or created concrete details and data that were inaccurate or exaggerated. It also regurgitated implicit and explicit biases against marginalized religious communities or intra-faith minorities.

As one participant summed it up, “I found AI to be more religiously illiterate than me, which is saying something!”

Where to from here?

Asked to consider why AI was found wanting in its accuracy in depicting American religious diversity, participants surmised that because AI is trained on what internet publics “know” and share about religion, it is just as religiously illiterate as the rest of us. They suggested it takes students of religion who are paying careful attention to help it along, correct its mistakes and continue to critically question the just-so narratives about religion, religions and the religious that can be found online.

In other words, participants discovered how AI amplifies and compounds some of the worst in religious illiteracy.

Writing for the Religion, Agency and AI forum, digital religion scholar Giulia Evolvi reminds us that in an age of hypermediation, “religious communication, like all modern communication, is no longer mediated linearly. Instead, digital media amplifies and reshapes it, creating intensified networks and narratives.”

Thus, in an age when more people will turn to AI to answer their questions about religion and spirituality, it is important that we engage with the technology, critique its biases and weaknesses and continue to pay attention to the ways humans employ the concept of “religion” to make sense of the world around them and their place in it.

Even with the advent of AI technologies — and religious studies students’ use of it — the why of studying religion doesn’t change. Religion remains interesting, intricate and important.

We might just need to shift some of the ways we go about making sense of it and adapt our classrooms and conversations accordingly.

When religious leaders die

For me, Jimmy Carter’s death came too soon.

Not necessarily because of his age. He lived to the ripe old age of 100 and, in many respects, lived those years to the fullest.

No, and if I may be crass for a moment, Carter passed before I had a reporting guide ready for reporters looking to cover the faith angles of his life and legacy.

You see, as Editor for ReligionLink, I put together resources and reporting guides for journalists covering topics in religion. Each month, we publish a guide covering topics such as education and church-state-separation under Trump, faith and immigration or crime and houses of worship.

Early in 2024, I started to put together a guide to cover the passing of Jimmy Carter. Serving as Editor is only a part-time gig, and it usually takes all the time I have dedicated to the role to produce a single, monthly guide. But on the side, I started to make notes, identify sources and build a timeline for Carter’s life and legacy.

When he passed on December 29, 2024, the guide was not ready. Nor would it be in the matter of days necessary for it to be useful. So, the opportunity came and went. The draft of the guide to covering Jimmy Carter’s passing tossed on the editing floor.

The missed occasion, however, inspired me to work ahead more intentionally on guides for other famous faith leaders. The process of putting such guides together led me to reflect on what it means to remember, and report on, the passing of prominent figures in religion.

Covering, and Questioning, Anti-Christian Persecution

If you report on religion long enough, you’re bound to be called an anti-Christian bigot at some point in time.

In my 14 years of reporting, I’ve been labeled an atheist agent for my coverage of a book on how Jesus may have been a vegetarian, denounced as a prejudiced partisan as I covered instances of clergy abuse in Houston, Texas, and much worse for my writing on neo-Nazi ideology and racism among Lutherans in Germany and the U.S.

In each case, the critique of my writing was less about the coverage or claims therein, but much more to do with a feeling that anti-Christian bias — and even persecution — in the media is not only real but rampant.

When it comes to the issue of anti-Christian persecution itself, coverage in the media can sometimes swing between two magnetic poles. On one end are those who are convinced that such persecution is the most pressing contemporary human rights issue. On the other are those who equate such statements as melodrama, with little grounding in the lived reality of most communities worldwide.

Journalists covering the issue might be swayed depending upon their sources, who often have a stake in arguing one way or the other.

To best cover the matter of anti-Christian persecution, or to address it when it comes up in critiques of our coverage, reporters have to make two things clear: 1) many individuals and communities across the globe are vulnerable because of their identification as Christians and 2) that the extent of anti-Christian persecution is not as widespread or as grievous as some make it out to be.

To help navigate how to cover particular cases and claims, I recommend journalists consider issues related to power, the shift from “privilege to plurality,” and how Christians use the idea of persecution as a way to make sense of their faith in the 21st century.

If Piety Is Always Political, Who Then Is A Saint?

On the outskirts of Naples, in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, lies the sanctuary of Madonna dell’Arco in Sant’Anastasia.

The walls of the shrine are covered in painted, votive tavolette — little, painted boards given as an offering in fulfillment of a vow (ex voto) and featuring devotional scenes and images of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Christ.

One of my favorites features a man in bed, with a heavily bandaged leg, his small children and wife praying to the Virgin and Child as they appear amidst a veil of clouds from their throne in heaven.

It is, in many ways, a visual embodiment of traditional notions of piety, defined as dutiful devotion to the divine.

But as I teach in my religious studies courses, piety can take a variety of forms.

It can be visual and sartorial, both highly personal and politically charged. More than an individual’s particular practice of religious reverence, piety is a socially defined and structured response to one’s emotional, social and material context. And in a time of political upheaval, social uncertainty and ecological anxiety, it might do well to revisit piety and its varieties.

Reporting on faith in polarized times

In a slight departure from my usual column at Patheos (“What you missed without religion class”), I was asked by my editors to respond to the following prompt, as part of their new initiative on Faith & Media:

“Faith Amid the Fray: Representing Belief Fairly During Polarized Political Times - Explore the role of media in shaping perceptions of faith during politically charged times. As we have a government in transition and the world becomes less stable, how should the media work to accurately reflect faith’s place in all this? ”

As outgoing president of the Religion News Association and Editor of ReligionLink — a premier resource for journalists writing on religion — I’ve spent time thinking about what religion reporters write about and how it’s best done.

Looking back on my 14 years on the beat, and looking ahead to the role of news media in shaping perceptions of faith in the politically charged times we have ahead of us, I believe religion reporters have the opportunity to approach the next year with “curiosity” — as The New Yorker’s Emma Green put it — and recommit to the balance, accuracy and insight that best characterizes our beat.

I encourage all those who care about faith and media in polarized times to take a deeper look at the link below…

Religion, Immigration and the 2024 Elections

Over the last six months, I’ve been covering religion and immigration for Sojourners Magazine.

I traveled to Tijuana, Mexico, Lampedusa, Italy, southern Arizona and downtown Los Angeles to hear from migrants making their way. I heard from Muslim aid workers on the front lines providing sanctuary and nuns serving the vulnerable asylum seekers living on the streets of Skid Row. I sat with mothers weeping over their children and praying for safe passage at a cemetery just meters from the bollard-steel border wall that rips through the Sonoran wilderness like a rust-colored wound.

In my latest for ReligionLink and as part of my “What You Missed Without Religion Class” series at Patheos, I reflect on what you need to know about faith and immigration ahead of the 2024 elections.

Image And Power, Satire And Sacrilege At The Paris Olympics

When I teach a religious studies class, I try to pull something from the headlines to use for discussion. You know, something religion-y to get students thinking about religion’s continuing ubiquity and importance in the world today.

Had I been teaching a class at the end of July 2024, there would have been only one option for that thing: the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics.

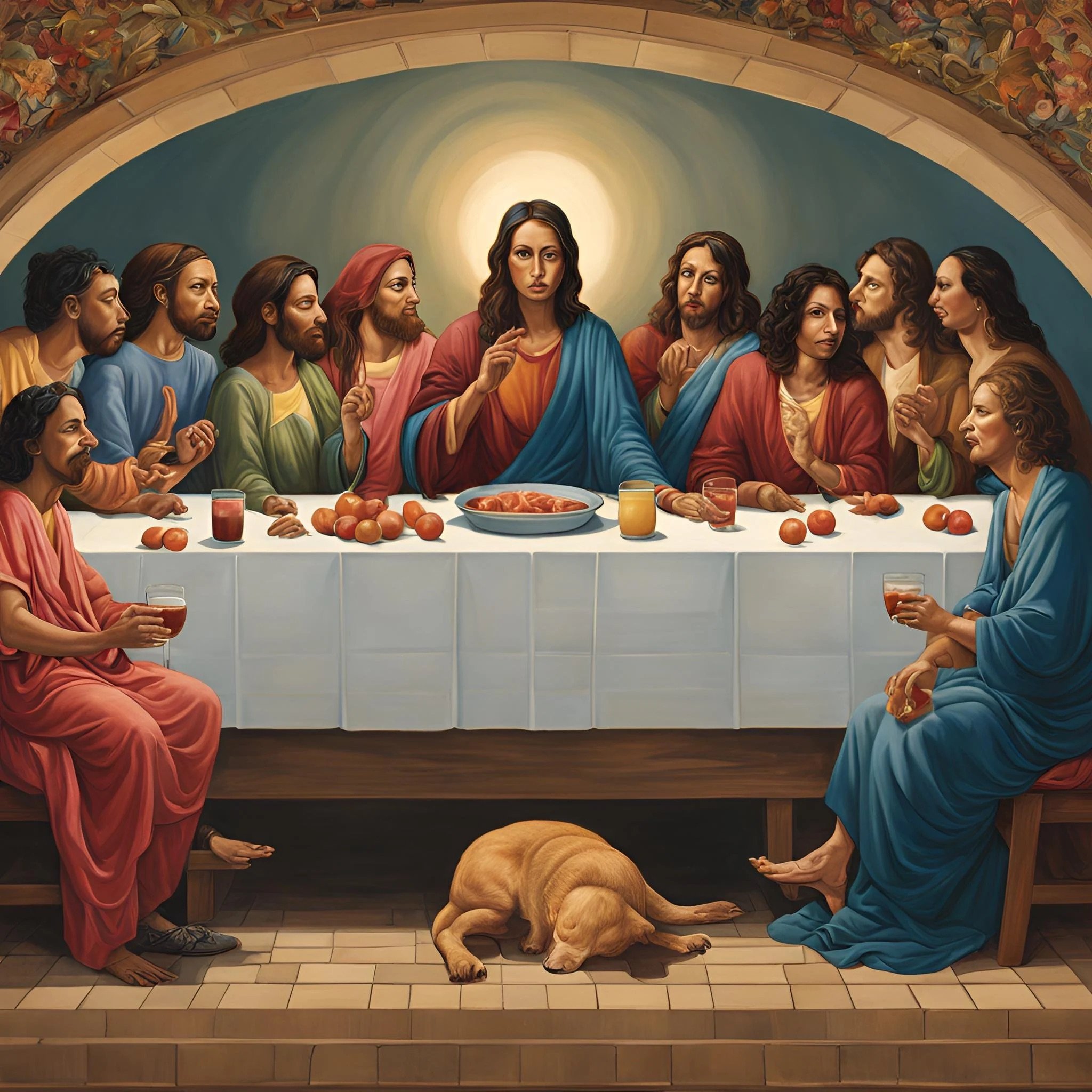

Not the bells ringing at Notre Dame Cathedral and not Sequana, goddess of the river Seine, galloping in gleaming silver with the Olympic flag. Worthy topics, to be sure. But none was more worthy of discussion — if social media were the measure of things — than a living tableau of LGBTQ+ performers posing in what seemed to be (or…possibly not) a recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

It created some conversation and controversy, to say the least. And rather than adjudicating the right- or wrongness of the artistic choice, the ins and outs of the potential offense, whether the portrayal was Ancient Greek or Renaissance Italian, or the dynamics of French secular culture, global Catholicism and U.S. evangelical culture (again, all worthy topics), I would have used the kerfuffle as a case study in the power of the image and the power of satire in the world of religion.

The power of image

With or without religion, images are powerful. They move us to anger, they move us love; they move us to buy, they move us to believe.

And in his eponymous book, religion scholar David Morgan discusses the power of the “sacred gaze” — a way of seeing that invests an object (an image, person, time or place) with spiritual significance. Across a variety of religious traditions, Morgan traces how images in different times and spaces convey beliefs and produce religious reactions in human societies – what he calls, “visual piety.”

As human products, images and religious ideas have grown together, with some images having the power to determine personal practice and identifications, rituals and notions of sacred space. As “visual instruments fundamental to human life,” images have their own materiality and agency. Think of the ubiquitous statue of the Buddha sitting in backyard or the glittery gold calligraphy of “Allah” or “Muhammad” hanging over a family’s living room; the brightly colored images of Ganesha and Krishna or a copy of Eric Enstrom’s “Grace” hanging in kitchens and cookhouses across the U.S.

Each of these images serve as markers of a whole range of social concerns, devotional piety, creedal orthodoxy or gender norms.

So too with da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” As one of the most well-known religious images the world over, the painting is not a part of any Christian canon. It isn’t even an accurate representation of what the Last Supper, as recorded in the Christian Gospels, would have been. Jesus’ disciples were not Renaissance European white men, they were probably not pescatarians, nor were they seated on one side of the table (or seated at that kind of table at all). But as a myth we knew we were all making, and as the National Gallery’s Siobhán Jolley pointed out on X, the painting morphed from being a sign (a painting portraying an interpretation of biblical texts) to a signifier (a bearer of meaning so pronounced that it came to visualize Jesus’ last meal with his followers for many).

And in our contemporary culture(s), such visual cues carry a particular kind of power. In a highly visual society, bombarded by the rapid consumption of images on screens of varying size and intensity, images can transcend one context and speak to many — as did the recreation of da Vinci’s “Last Supper” (or…maybe not) when it resonated both positively and negatively with so many.

As a visual quotation of a popular image, we translated its meaning and the image spoke with power to various communities and subcultures. It tore people up and took the internet by storm. It manifested opprobrium and offense, celebration and adulation, as it was read as a sacrilege of the highest offense or as a symbol of vibrant tolerance and pleasing subversiveness. Along the way, it created a whole range of responses, on what is and what is not offensive, what is and is not idolatry, what is and is not Christian privilege, what is and is not persecution; the list could go on and on.

For all that it was (or was not), the Opening Ceremony moment (and it was, after all, but a blip on the screen) illustrated once again the power of religious images, even in increasingly secular societies.

The power of satire

In addition, whatever the performance was meant to represent, it was almost certainly meant as a form of satire.

A genre with generations of history, religious satire’s power lies in its ability to direct the public gaze to the vice, follies and shortcomings of religious institutions, actors and authority writ large. Whether calling out hypocrisy or corruption, religious satire has been used for centuries to take religious elites or established traditions to task.

Examples of savage satire and nipping parody abound across religious history. From the Purim Torah and its humorous comments read, recited or performed during the Jewish holiday of Purim to "Paragraphs and Periods,”(Al-Fuṣūl wa Al-Ghāyāt) a parody of the Quran by Al-Ma‘arri or the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer or Robert Burns’ poem “Holy WIllie’s Prayer,” authors and authorities, playwrights and poets have wielded scalding pens to critique what they see as the hypocrisy, self-righteousness and ostentation of religious communities.

As such, satire has been powerful as a means of protest both from without and within religious traditions. For example, the 16th-century rebel German monk and Reformer Martin Luther used his caustic touch to call what he thought were abuses within the Catholic Church to task. Jeering and flaunting his way through theological controversies and the dogmatic discussions of his day, Luther was not one to skirt the issue or back away from using humor and satire to prove his point. In fact, he was well known for his use of scatological references, offending his followers and opponents with vulgar references to passing gas and feces.

Each of these examples shows how satire relies on a combination of absurdity, mimicry and humor to highlight the problems its creators see with religious actors’ or institutions’ behaviors, vices or social standing.

To that end, the opening ceremony’s display was religious satire par excellence, insofar as it pushed a particular social agenda and advocated for certain recognitions for a marginalized community through its exhibition. The living display not only created a stir but captured the public imagination, sparking discussion and debate about Christian privilege, European culture and the acceptance and affirmation of LGBTQ+ individuals in religious communities. In this way, religious satire can also help create community and a sense of belonging among those who are in on the joke and jive with the critique embodied in the satire.

The persistent power of religion

The debate around the tableau will (hopefully) die down in the days and weeks to come (and perhaps already has in a media cycle that serves up a fresh controversy every 24-hours). But if I were to point to just one lesson in my religious studies classroom, I would highlight how the scene — for all it was or wasn’t — proved once again the power of images and satire in the field of religion.

It is another case study in how, even at supposedly “secular” events in a decidedly “secular” country, religion — and the primary and secondary images and satire thereof — remains persistently present and ubiquitously potent. And that, dear students of religion, is something to keep in mind for the next controversy, which is sure to come sometime soon.

A Cross In The Barbed Wire: Mixed Reflections On Faith & Immigration

In February 2019, Miguel stared out at the San Pedro Valley in Mexico, stretching for miles below him from his position on Yaqui Ridge in the Coronado National Monument. Standing at Monument 102, which marks the symbolic start of the 800-mile-long Arizona Trail, Miguel remarked on how the border here doesn’t look like what most people imagine.

Instead of 30-foot bollards, all one finds is mangled barbed wire to mark the divide between Arizona and Sonora. Here hikers can dip through a hole in the fence to cross into Mexico, take their selfie, and pop back over.

“It’s as easy as that,” Miguel said, with a melancholic chuckle.

But for Miguel’s mother the crossing was not only difficult — it was deadly. She perished trying to find her way to the U.S. across the valley’s wilderness when Miguel was just four years old and already living in the U.S. with his father.

Not knowing exactly where she died, Monument 102 became a makeshift memorial for Miguel’s mother, the obelisk marking the U.S./Mexico border a kind of gravestone. The barbed wire itself even holds meaning for Miguel. “When I come every year to remember her,” he said, “and the knots in the barbed wire remind me of the cross.

“It may sound strange, but that gives me comfort,” he said.

Miguel is far from alone in making religion a part of the migrant’s journey. As migrants move around, across and through borders and the politics that surround them, religious symbols, rituals, materials and infrastructures help them make meaning, find solace and navigate their everyday, lived experience in the borderlands.

With immigration proving a top issue for voters in the U.S. and Europe this year, this edition of What You Missed Without Religion Class explores the numerous intersections between religion and migration.

What's behind the rising hate?

At the end of last year, the uptick in antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in the U.S. and around the globe captured headlines as part of the fallout from the Israel-Hamas war.

Reactions were swift and widespread, as university presidents resigned, demonstrators took to the streets in places such as Berlin and Paris and the White House promised to take steps to curb religious and faith-based hate in the U.S.

The topic of rising discrimination and incidents of hate remains contentious, as political polarization and debate over definitions challenge reporters covering the issues.

But before we come to conclusions, it’s important to consider a) what we are talking about - or - how we define antisemitism and Islamophobia and b) the long arc of “Other” hate across time.

In the latest editions of ReligionLink and “What You Missed Without Religion Class,” I unpack both so we can better understand and react to the surge in hate.

Tomorrow’s religion news, today

At the beginning of last year, I predicted the Pope would be big news in 2023.

While I thought it would be because of his declining health and increased age, it turned out that Pope Francis had big plans to cement his long-term hopes for renewal, which are likely to outlast his pontifical reign.

In 2023, Pope Francis remained busy, traveling widely, convening a historic synod, denouncing anti-LGBTQ+ laws and approving letting priests bless same-sex couples, overseeing the Vatican repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery and facing various controversies.

For all the above, he was named 2023’s Top Religion Newsmaker by members of the Religion News Association, a 74-year-old association for reporters who cover religion in the news media.

Beyond Francis and the Vatican, there were other major headlines in 2023: the Israel-Hamas war, along with the rise in antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in the U.S. and around the globe, ongoing legislative and legal battles following last year's Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, the exodus of thousands of congregations from the United Methodist Church and the nationwide political debates over sexuality and transgender rights and the Anglican Communion verging on schism.

While it is one thing to look back on the top religion stories of the year, what about predicting — as I did with the Pope — what will be the big religion news in 2024?

In 2024, we will see ongoing wars in places like Gaza, Ukraine, Yemen and Nargono-Karabakh continuing to capture headlines. So too the state of antisemitism and anti-Muslim discrimination. The ubiquity and uncertainty of artificial intelligence should also be on our radars, as should news related to the intersections of spirituality and climate change, the fate of global economies and how religious communities adapt to the ruptures and realignments associated with an increasingly multipolar world.

For more on my predictions, as well as additional sources and resources to explore, click the link below.

And to go even deeper into 2024’s religion predictions, you can explore my analysis of religion’s role in ongoing conflicts, upcoming elections and more by checking out my column, “What You Missed Without Religion Class.”

A bust of Martin Luther in Eisleben, where he was born, baptized and died. Shortly before his death on 18 February 1546, Luther preached four sermons in Eisleben. He appended to the second to the last what he called his "final warning" against the Jews. (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

A critical look at Luther Country

It’s pretty boujee, but I have two stained glass windows in my office.

I know, I know.

But one of them is pretty much tailor made for a religion nerd like me. It’s a bright and beautiful, stained-glass representation of the Wartburg Castle.

Perched at a height of some 400m above delightful countryside and rich central German forest, south of the city of Eisenach in Thuringia, the Wartburg is “a magnet for memory, tradition, and pilgrimage,” a “monument to the cultural history of Germany, Europe, and beyond.” Christians the world over also know the castle as where Martin Luther made his momentous translation of the Bible over the course of eleven weeks in the winter of 1520-21.

Since moving to Eisenach, I’ve watched out my windows — the non-stained ones — as busloads of tourists from places like South Korea, the U.S., and Brazil arrive on the square outside my apartment, where a prominent statue of Luther awaits them. They are here, in Luther Country, to walk in the Reformer’s footsteps and learn from his life in towns like Wittenberg and locales like the Wartburg.

A lot of these tours lavish praise on Luther, lauding the 16th-century rebel monk and cantankerous theologian for birthing the Reformation, and shaping Germany and the wider world’s theological, linguistic, historical, psychological and political self-image in the process.

And rightly so. Luther’s legacy is long and important to understand. But I can’t help but wonder what these tours would look like if they were a bit more critical of the man and his consequence. What, I often muse, would a more critical Luther tour look like?

Who said anything about an apple tree?

As the annual Reformation Day approaches (October 31) and I get ready to host a group of college students in Eisenach here to learn about Luther and his impact, I’ve been thinking about how our vision of Luther can be skewed by the superficial stereotypes that are typically trotted out for people on the usual tours.

It’s not that I blame the tourists, travelers, and pilgrims themselves. It’s hard to see past the Luther-inspired gin, “Here I Stand” socks, and cute Playmobil toys to disrupt the narrative around the Reformator.

The well-known statue of Martin Luther in Lutherstadt-Wittenberg, in central Germany. Some commentators suggest it shows — with the word “END” written so prominently under the words “Old Testament” — a questionable view of the Bible “in a political and social context in which anti-Jewish views are again on the rise.” (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

But the resources are there, if we care to see them, to startle and awaken our appreciation for who Luther was in critical fashion – to move beyond the myths we know we are making to (re)evaluate Luther and the ways in which we’ve made him into a caricature for our own purposes.

We all make claims about ourselves and others, doing so from within practical, historical, and social contexts. Stories around Luther are no different. When we talk about Luther, it is less about the man, his thought, and his supposed authority over theology and history itself. Instead, it is much more about the ongoing process by which we humans ascribe certain things to people like him: certain acts, certain status, certain deference.

Many of the stories and claims about Luther have calcified over time, produced and reproduced in books and movies, within theological writings and on tours in central Germany.

The good news is, they have also been contested, undermined, and — in some instances — replaced.

Some of these have been relatively simple things, like the fact that Luther was no simple monk, but a trained philosopher and theologian. Or, that he never nailed ninety-five theses to a church door in Wittenberg or said, “Here I stand!” or anything about planting an apple tree. These are, as Dutch church historian Herman Selderhuis wrote, fine sentiments and sayings, but just not true or attributable to Luther himself.

Luther: Wart(burg)s and all

There are also darker and more difficult subjects in need of revisiting in our retellings of Luther’s life — issues that bear relevance to contemporary conversations around race and class, diversity and difference.

As PRI reported, appreciating who Luther was also means coming to terms with how he “wrote and preached some vicious things about Jews.” In his infamous 1543 diatribe “Against the Jews and Their Lies," Luther called for the burning of Jewish synagogues, the confiscation of Jewish prayer books and Talmudic writings, and their expulsion from cities. It is possible that these directives were immediately applied, as evidence suggests that Jews were expelled from the town of his birth, Eisleben, after he preached a sermon on the “obdurate Jews” just three days before his death at age 62.

Luther’s death mask in Halle, Germany (PHOTO: Ken Chitwood)

Dr. Christopher Probst, author of Demonizing the Jews: Luther and the Protestant Church in Nazi Germany, said that while Luther’s “sociopolitical suggestions were largely ignored by political leaders of his day,” during the Third Reich “a large number of Protestant pastors, bishops, and theologians of varying theological persuasions utilized Luther’s writings about Jews and Judaism with great effectiveness to reinforce the antisemitism already present in substantial degrees.”

Probst said that one theologian in particular, Jena theologian Wolf Meyer-Erlach, “explicitly regarded National Socialism as the ‘fulfillment’ of Luther’s designs against Jewry.”

Today, far-right parties continue to use Luther’s image and ascribed sayings to prop up their own political positions.

Beyond his tirades against Jewish people and their sordid use in German history, we might also take a critical look at the class dynamics at work in Luther’s life. Historically, his family were peasant farmers. However, his father Hans met success as a miner, ore smelter and mine owner allowing the Luthers to move to the town of Mansfeld and send Martin to law school before his dramatic turn to the study of theology. How might that have shaped the young Luther and later, his response to the Peasants War in 1524-25? How might it influence our understanding of who he was and what he wrote?

There are also critical gems to be found in his writings on Islam and Muslims, his encounters with Ethiopian clergyman Abba Mika’el or the shifting gender dynamics at work in his relationship with Katharina von Bora, a former nun who married Luther in 1525.

Reimagining Luther Country

Thankfully, I am far from the first person to point these things out. Museum exhibits, books, and documentaries have covered these topics in detail, doing a much more thorough job than I have above.

The problem is that gleanings from these resources can struggle to trickle down to the common tour or typical Luther pilgrimage. Or, they’re ignored in favor of just-so stories.

In Learning from the Germans, Susan Neiman wrote about the power of a country coming to terms with its past. In her exploration of how Germans faced their historical crimes, Neiman urges readers to consider recognizing the darker aspects of historical narratives and personages, so that we can bring those learnings to bear on contemporary cultural and political debates.

We might consider doing the same as we take a tour of Luther Country — whether in person or from afar. By injecting a bit of restlessness into our explorations, stirring constantly to break up the stereotypes, being critical and curious and exploring outside the safe confines of the familiar, we might discover more than we bargained for. But that, I suggest, would be a very good thing.

By telling different stories about Luther — and by demanding that we be told about them — I believe we might better know ourselves. How might we relate to a Luther who is not only the champion of the Reformation, but a disagreeable man made into a hero for political and theological purposes? How might that Luther speak to our times and the matters of faith and politics, society and common life, today?

As we come up on Reformation Day — and I welcome that group of students to my hometown and all its Luther-themed fanfare — I hope we might lean into such conversations and recognize how a critical take on Luther might prove a pressing priority for our time.

Does the world really need interreligious dialogue?

Growing up in what could best be described as a decidedly non-ecumenical Protestant denomination, I was taught to treat “interfaith” like a bad word.

But the negativity around interactions between people of different religious, spiritual and humanistic beliefs always sat a bit awkwardly with my everyday experience growing up in Los Angeles, one of the most religiously diverse cities in the United States.

I couldn’t square the alarming discourse around interreligious interactions with the lived reality of diversity that defined my teenage years (and beyond). My friends were Buddhist and Muslim, Jewish and Christian, Pagan and atheist.

And so, despite the warnings, I stayed curious about different traditions, learning about other religions as I dove deeper into my own.

As I’ve made religion my profession, I’ve also come to appreciate how interreligious dialogue has changed over the years and how it is far from the caricature I was brought up to believe it was.

On the occasion of the 2023 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago (August 14-18), I shared some thoughts on interreligious dialogue and its role in the contemporary world on my column, “What You Missed Without Religion Class.”

Interfaith dialogue often gets a bad rap as a project concerned with surface level “feel good” conversations. Today, interreligious dialogue (a more widely preferred term) has grown into a multifaceted and critical field of interaction with real-world impact and implications for your life and mine.

Should we be comparing Islam and Christianity, the Bible and the Quran?

The other week, I was talking with a friend of mine who is pastor of an evangelical congregation in Texas.

He was asking for my input on a multi-week series comparing different “world religions” with Christianity at his church.

Numerous, well-meaning pastors, lay leaders, and teachers like my friend have led such comparative studies in their own communities as a means to help Christians navigate contemporary religious pluralism. I even led a few of my own in my early days. While most of the leaders of these studies start with the intention to help their parishioners learn more about the world's religions, the way they go about it usually leads to nominally increased religious literacy. Even worse, these studies can exacerbate pre-existing prejudices or presuppositions about the religions they set out to better understand.

Which raises the question of whether there is any promise to comparing things like Christianity and Islam, the Quran and the Bible at all. The problem, I suggest, might lie in the very act of comparison itself.

Photo by Grant Whitty on Unsplash.

Religion in Your Face: Ash Wednesday and the Practice of Religious Facial Marking

Several years ago, when I was living in Houston, TX, a man walked up to me at a local café and kindly said, "Excuse me sir, you've...um...I think you have dirt on your face."

He was half right.

It wasn’t exactly dirt, but ashes. Ashes smudged on my forehead in the shape – if you looked at it just right and from a 43-degree angle – of a cross.

One could not blame the man for mistaking my visible marker of inward penance and outward allegiance to a particular strand of religiosity…for dirt.

These days, in places like H-town, you don’t see too many people wearing their religion on their face.

Nonetheless, later this month (February 22, 2023) millions of Christians across the world -- Catholic, Lutheran, Anglicans, others – will also don gray smudges on their brows to commemorate Ash Wednesday.

Traditionally viewed as the start of Lent – a 40-day penitential season of fasting and preparation preceding Easter – Ash Wednesday is most widely associated with the "imposition" or "infliction" of ashes on practitioners’ foreheads.

Christians, however, are not alone in marking their faces with religious symbols. There are traditions in India, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere that involve religious symbology born on foreheads, cheeks, and chins.

While such outward signs of devotion may seem an extreme in our seemingly secular age, more often than not, these religious facial markings tell us relatively little about the “inner religion” of the devotee and much more about spiritual symbols’ social function(s).

The Past, Present, and Future of Religion

Every year, numerous pundits and forecasters offer their crystal-ball takes on financial futures, political potentials, and what they think will be the calendar-defining or epoch-making events in the year to come.

But what about religion?

As 2022 ended, I had the chance to look back on, and forward to, the year in religion.

Working with the Religion News Association (RNA) – a 73-year-old trade association for reporters who cover religion in the news media – I helped oversee a poll of its membership on the top religion stories over the previous year. Then, in my capacity as Editor for ReligionLink – a monthly resource for reporters writing on religion – I put together some predictions for the big religion news to come in 2023.

The two experiences gave me an opportunity to reflect on religion’s persistent and ubiquitous role in global events. They also underscored once more how a basic knowledge of religion is not so much about understanding worlds beyond, but the world we live in right now.

Your 2022 Favorites: The Religion + Culture Top Ten

Back in 2007, I started a blog I hoped would become my first book (blogs are what we did back in the aughts, kids).

My grandma was a faithful reader. So were a few friends. Other than that, you might say not much came of the experience. The book did not work out, the stats were flat, and the writing was sometimes…oof.

What did come out of the blog was a joy for sharing through writing, opening worlds to others through words, and creating a community online.

I’ve been publishing my work online ever since. Now, as a professional religion nerd (a.k.a., religion newswriter and scholar), I continue to be humbled by those of you who take the time out of your day to read what I have to share.

The past year was no different. From predictions about what religion headlines would capture our imagination to spirit tech trends, exploring Morocco’s architecture with the “Prince of Casablanca” to traipsing around Berlin in search of its soul, I got to share some cool stories in 2022.

A blogger at heart, I share all my publications here on KenChitwood.com. Over the last twelve months, some caught your attention or imagination more than others. As 2022 comes to a close, I thought I’d share them with you again as the Top Ten Religion + Culture Stories.

Looking at the list below, your tastes range widely. The religious contours of the war in Ukraine featured twice in the list to no surprise, but otherwise we have selections on the limits and dangers of religious freedom, modern paganism, interreligious dialogue, global Islam, American Christianity, airport spirituality, Mormon missionaries in Berlin, and James Bond’s spirituality.

Y’all are such interesting people. Really. I can’t wait to catch up with you at a cocktail party to discuss the stories below. Until then, take a moment to revisit some of your favorite stories from 2022 or jump in for the first time (and share them with your friends at that cocktail party, in case I can’t make it).

Thanks again and cheers, friends. 🥂Until 2023!

“God puts us here especially for such moments”

Christians Respond to War in Ukraine

Religion, James Bond religion

Does 007 take his Christianity shaken, not stirred?

War in Ukraine

Covering the conflict’s religious contours.

And, an honorable mention…

Who are the exvangelicals?

Understanding the exodus from contemporary U.S. Christianity.

Spirit Tech is here to stay

In our house, we have a new laptop.

It’s shiny and new, with a fancy blue OLED touchscreen and widgets galore.

Perhaps you too — not long after “Black Friday” and “Cyber Monday,” nor long before the festive, gift-giving season — will be purchasing new tech.

Maybe a new smartwatch? The latest video game console? How about a meditation headset from tech startup Muse?

Yep, you read that right. The Muse headband is a brain-sensing device that provides real-time neurofeedback during meditation sessions or, as the company promises, to help you focus, sleep, or otherwise reach peak performance.

It is one of many technological innovations promising to trigger, enhance, accelerate, modify, or measure spiritual experiences and deliver more peace and progress in the process.

From brain stimulation to synthetic psychedelics, new spiritual movements in Silicon Valley to the everyday ways technology is used in worship and devotion technology is changing the way we do religion.

This is what researchers Kate Stockly and Wesley Wildman of Boston University’s Center for Mind and Culture call “spirit tech.”

Not only do they believe “spirit tech” is here to stay, they also suggest it has the potential to heal our relationship with technology and radically alter the way we think and pray.

Recently, I had the opportunity to dive deeper into the world of “spirit tech,” writing two pieces to help you explore the wide world of religious technologies, their meaning, and their potential futures.

But wait...is it a cult?

When I first moved to New Zealand to work with a Lutheran parish in Palmerston North, I came across some FAQs – frequently asked question – on the national church body’s website.

Along with the usual queries, I found one peculiar bullet point. It asked: are Lutherans a cult?

Granted, Lutherans can be strange people. With their penchant for sneaking carrots into Jell-O salads and an often-disconcerting fealty to European heritages, Lutherans are anything but normal.

But rarely, if ever, had I heard them called a “cult.”

Numerous communities and religious bodies have been labeled with the pejorative term over the years. From Jonestown to Aum Shinrikyo, the Manson Family to Raëlism, the Church of Scientology to Heaven’s Gate, the Branch Davidians to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and yes, Lutherans – all of these, at some point in time, have been labelled a “cult.”

Which is not a term you want used for your community.

Why? Because it immediately suggests things like brainwashing, mass suicide, and crazy-haired white dudes stockpiling women, weapons, and weed in the backwoods.

Therein lies the problem.

When we hear the term “cult” we already think we know everything there is to know about that group. They’re dangerous. They’re deviant. They don’t deserve to be called a “real” religion.

But if we take a moment to double-click on the term and expand on what it means from a social perspective, we might find that the word "cult" – or "religion" for that matter – doesn’t mean what we think it means.