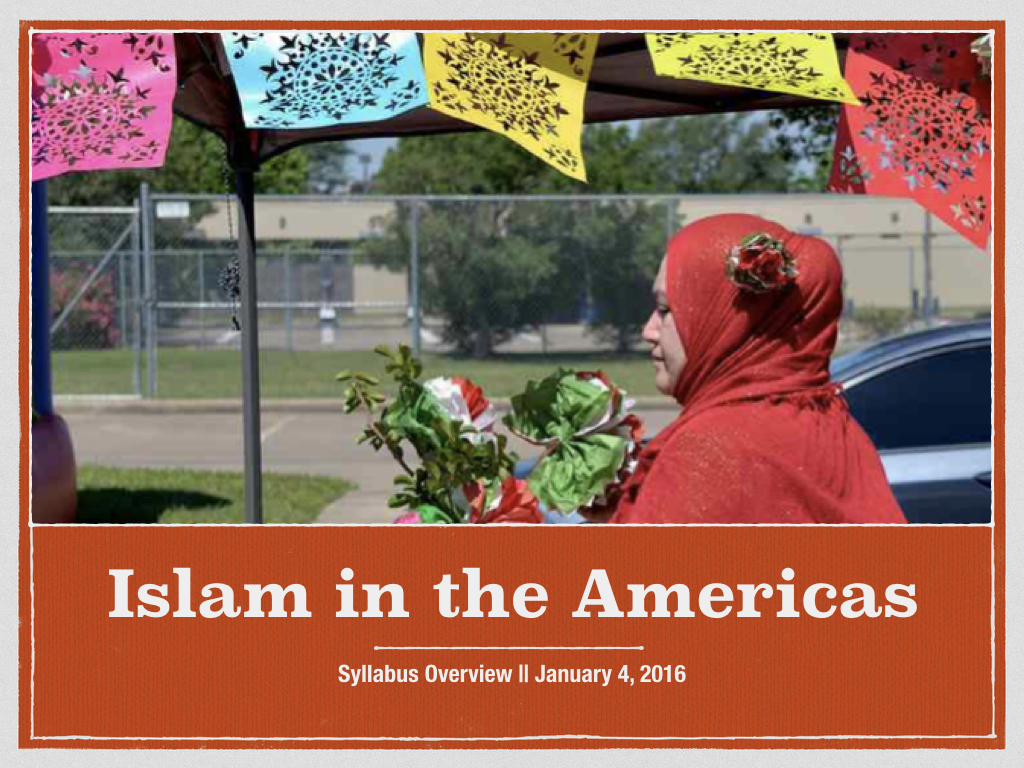

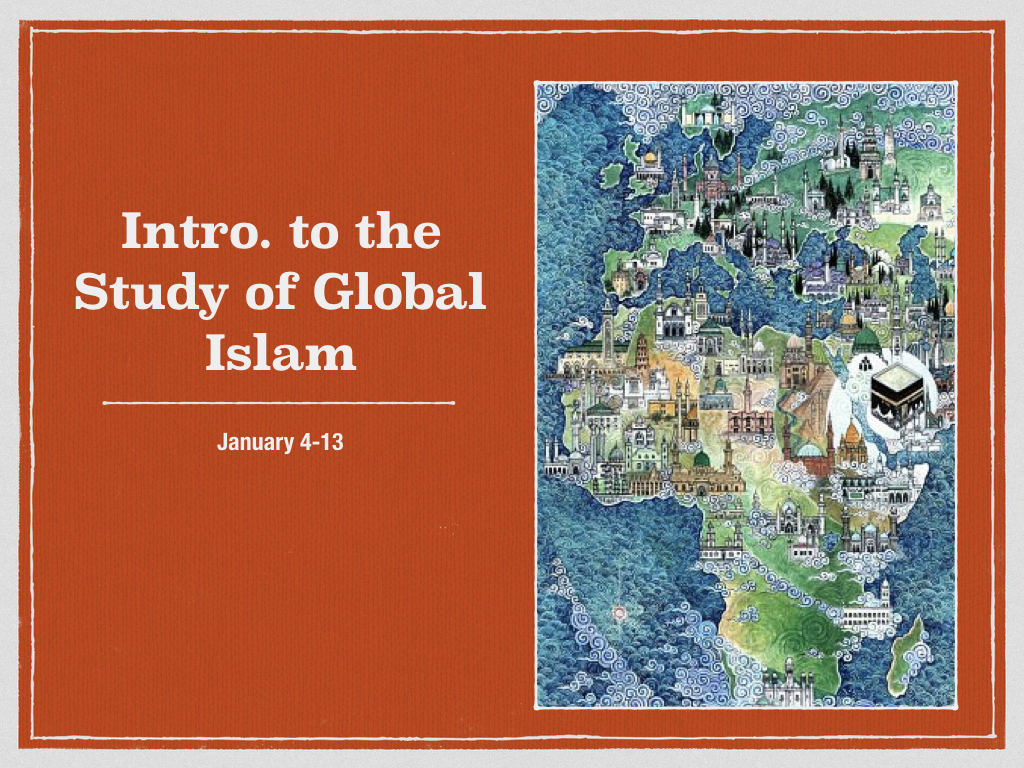

Why does Islam matter in the Americas? When did it arrive here? What values, practices, traditions, & tensions exist within its histories & social dynamics in the West? How can we study Muslim communities in this hemisphere?

In Spring 2017 I will offer a course called, "Islam in the Americas" (REL 4393/LAS 4935) with the UF Religion Department and in association with the UF Center for Latin American Studies. The lecture period will be every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from 9:35-10:25am (coffee is encouraged. Donuts are accepted as bribes...just kidding...kind of).

This course will place Latin America, the Caribbean, & North America within a broader Islamic framework & locate Muslims of various backgrounds & experiences within the hemisphere from the 1500s to today, from Cape Columbia, Canada to Catamarca, Argentina, & many periods & places in between.

The semester will be divided into four main parts: 1) studying global Islam; 2) theoretical themes in the study of religion in the Americas; 3) the history of Islam in the Americas; and 4) country/region specific cartographies of contemporary American Muslim populations.

n attempting to locate, and explore, Islam in the Americas students will first have to apprehend a bit of what it is to study "global Islam." In this introductory part of the course we will spend some time discussing what "Islam" is, what its main texts, traditions, and shared vocabulary are, and how studying Islam globally often means studying Muslim communities locally, but being sure to set them within macro-contexts at the regional, hemispheric, or global levels as well.

Studying Islam in the Americas will also require a theoretical foundation. This second part of our course will cover the heritage and contact of multiple cultures in the Americas -- both across the hemisphere and the Atlantic ocean. In order to do so, we will take a look at the heritage of Europe (specifically al-Andalus), North and West Africa, and other transnational ties via politics, economics, ideologies, technology, and more.

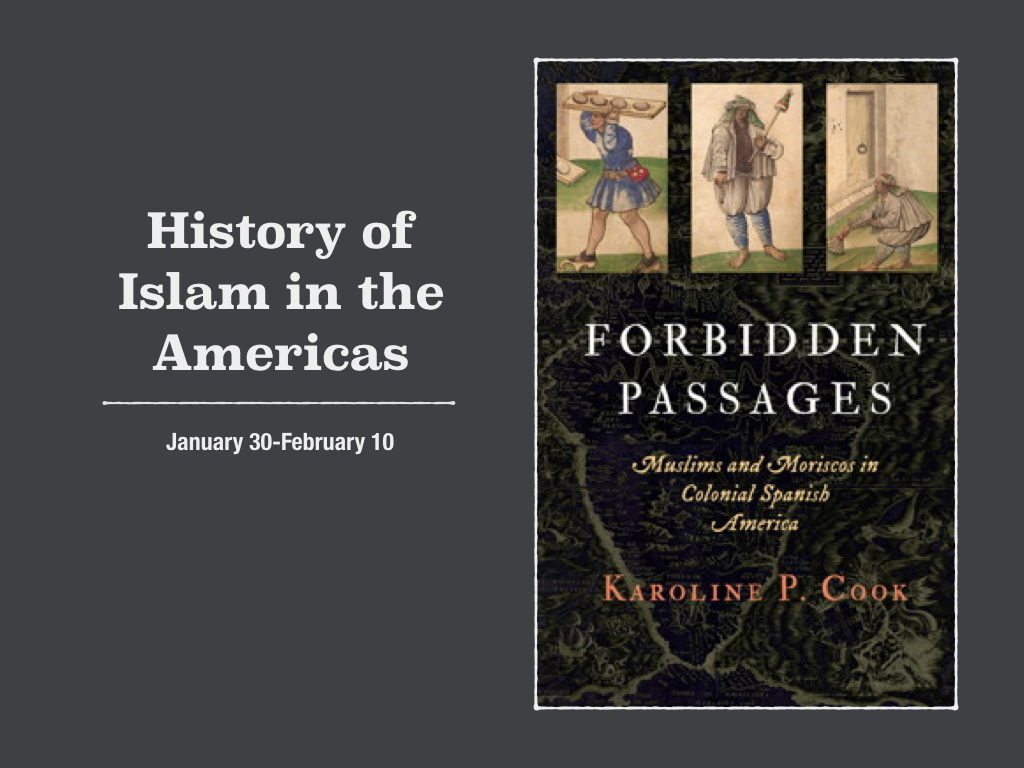

With these foundational aspects in place we will then dive into the study of the history of Islam in the Americas, the third section of course. Looking back to pre-colonial contact with Europe, we will navigate the "deeper roots" of Islam in the Americas that are largely ignored in historical overviews before delving into the "forbidden" and forced passages of Muslims across the Atlantic as conquistadors, slaves, and monsters in the Western imagination. Once here in the hemisphere we will see how Islam took part in, shaped, and was molded by its American context even as Muslims adapted to, resisted, and surrendered to the broader Euro-American worldview and its attendant lifeways.

In the final part of the course we will take a closer look at specific countries and regions ranging from North America to Latin America and the Caribbean. Specifically we will consider constituencies in Brazil, Mexico, Suriname, Trinidad, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the U.S., and Canada.

Over the course of the semester there will be ample opportunity for students to read and respond, discuss and deliberate the topics via various assignments. However, a semester capstone project, which will be worked on, edited, and completed throughout the course of the spring, will be presented via a final paper and presentation. These projects can take up any number of thematic, chronological, demographic, or geographic topics.

It is my hope that this course will help place Latin America, the Caribbean, and North America within a broader Islamic framework and locate Muslims of various genealogies within the hemisphere over the longue durée. urthermore, this course will aim to focus on local values, practices, traditions, and tensions placing these within larger questions about what kinds of histories, social dynamics, and meaning production make Islam significant, or how its significance is denied, in a part of the world that hasn’t recognized its history here or its contemporary configurations or impact.

If you have any questions, comments, or want to know more about the texts, assignments, or expectations for the course, please do not hesitate to contact me.